By Oluwaseun Taiwo

Every election season, Nigeria likes to boast about being Africa’s largest democracy. Yet when you look closely, the picture feels incomplete. Women make up almost half of the population, but in the corridors of power, they are nearly invisible. In the current 10th national assembly, only 19 out of 469 legislators are women, just 3.8 per cent. In the House of Representatives, there are only 15 women out of 360. In the Senate, only 4 out of 109. Across all 36 states, we do not have a single female governor. And in our state houses of assembly, out of 991 seats, only 45 are occupied by women. That’s a mere 4.5 per cent[1].

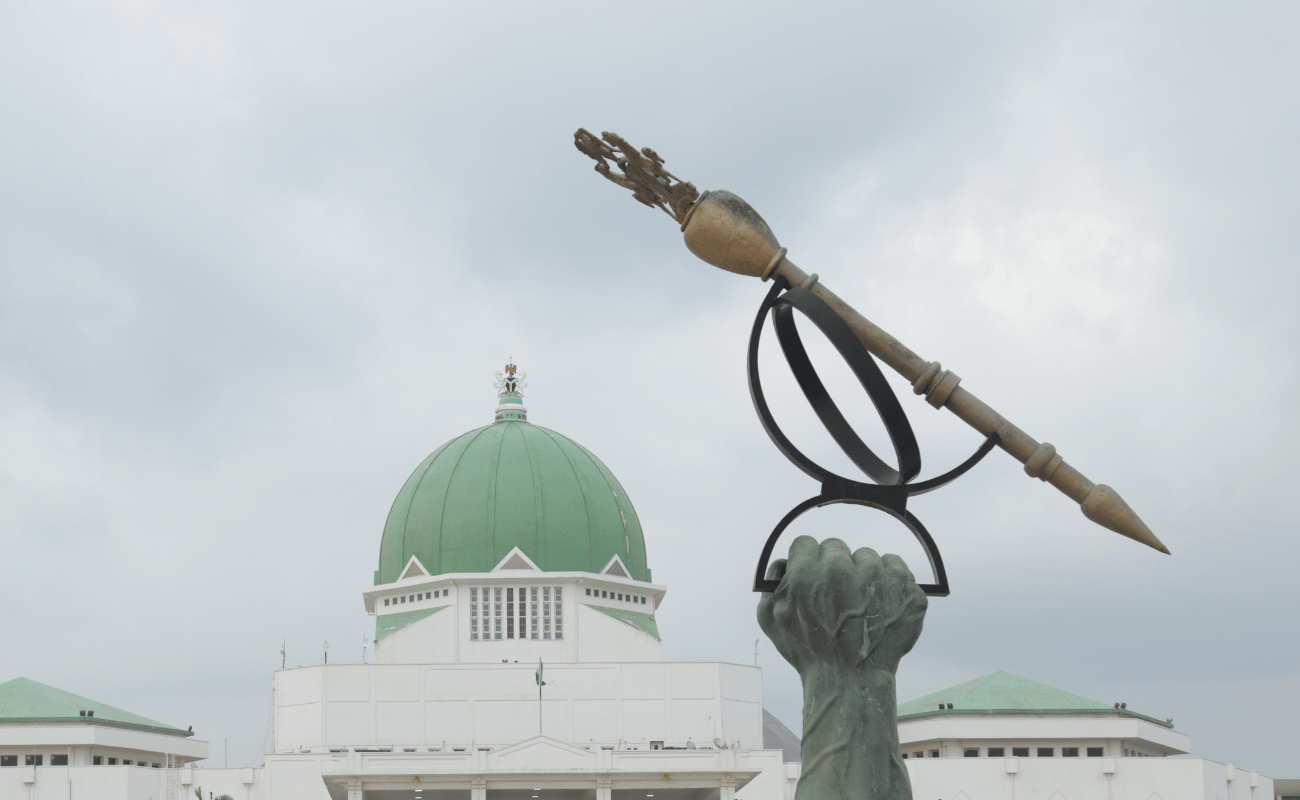

Now enters the “Special Seats Bill”, Nigeria’s latest attempt at correction. Also called the “Reserved Seats for Women Bill”, it proposes creating new positions in the National Assembly and state legislatures that only women can contest. Each state would elect a woman Senator and a woman House member into these new seats, while state assemblies would gain their own reserved positions. It’s designed as a temporary measure, subject to review after a few cycles, but even in its modest form, it has shaken Nigeria’s political waters.

And it should. Because when you zoom out, the statistics are frankly embarrassing. Nigeria’s position among Sub-Saharan African Countries in this ranking. According to this ranking by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) dated February 1, 2024, Nigeria is 180 out of 185 countries in terms of the number of women in its Parliament. With this position, Nigeria is the lowest-ranked Sub-Saharan African country in terms of the number of women in Parliament[2].

September 2025 showed that women are done waiting politely. The National Assembly’s public hearing on the bill turned into a platform for advocacy groups and ordinary citizens to speak up. Outside, the streets of Abuja were filled with chants, placards, and peaceful protests. Some rallies drew hundreds, others over a thousand. What struck most was the energy: women weren’t begging for favours; they were demanding fairness. They were saying, in essence, democracy without women is a broken promise.

Supporters of the bill argue it’s the quickest way to stop bleeding. Left on its own, Nigeria’s electoral system is unlikely to produce more than a handful of female winners each cycle. Reserved seats could instantly boost representation and provide women with a platform to prove their capabilities. But here’s where caution kicks in. Reserved seats are not a magic wand. They risk becoming a convenient shortcut for political parties that don’t want to do the harder work of reform. Imagine a party stuffing all its women into reserved seats and continuing to hand the “real” constituencies to men. That would be tokenism in its purest form. If Nigeria passes this bill, it must also hold parties accountable for fair primaries, transparent candidate selection, and protection against political violence. Otherwise, we’ll end up with numbers that look good on paper but don’t change the system.

Critics also worry about logistics. How do you carve out new constituencies without confusing voters? Can the Independent National Electoral Commission, already stretched thin, handle new ballots, new districts, and the required voter education? These are fair questions. Nigeria’s elections don’t exactly run like Swiss trains, more like Danfo buses on a rainy day, unpredictable, chaotic, and often frustrating.

Still, it’s hard to argue that Nigeria doesn’t need bold action. Look across Africa and the evidence is clear. Rwanda’s deliberate push transformed its parliament and reshaped national debates. Uganda’s district-level reserved seats have given women visibility and influence, even if inequality still lingers. Tanzania’s “special seats” system isn’t perfect, but it has guaranteed women a foothold in politics for decades. None of these systems solved everything, but all of them moved their countries forward. Nigeria’s refusal to act has left it stuck near the bottom of global rankings.

So where do we stand? The Special Seats Bill is necessary but not sufficient. It’s the scaffolding, not the finished house. Nigeria should pass it but also see it as a first step toward deeper reforms: cleaning up party nomination processes, fixing campaign finance, and tackling the culture of violence that scares women away from politics. Without those changes, reserved seats will be little more than patches on a leaking roof.

But imagine, just for a moment, a Nigeria where women make up 30, 40, or even 50 per cent of parliament. Imagine debates that reflect the realities of all citizens, not just men. Policies on healthcare, education, family welfare, and security would carry different weights. Democracy would finally start to look like the people it claims to represent.

The Special Seats Bill won’t deliver all of that overnight. But it could open the door wide enough for Nigerian women to step in, stay in, and change the conversation.

The real question is whether Nigeria’s leaders are brave enough to open that door or whether they will continue to hide behind excuses while half the nation remains locked out.

[1] Benjamin Kalu: Women occupy 19 out of 469 n’assembly seats — that’s painfully low | TheCable

[2] PLAC Production: Nigeria is the Lowest Ranked Sub-Saharan African Country on the Number of Women in Parliament – PLAC Legist