By Thomas Matthewson

Russia propaganda, in the form of misinformation, is weakening the fabric of truth and democracy across Africa. Such campaigns are not simply missions of international public diplomacy, whereby one country seeks to maintain a positive image towards the population in another, usually through legitimate propaganda. These campaigns are targeted and coordinated operations, part of Russia’s intentions to politically influence the continent. That is not to say other external powers in the past haven’t misinformed African countries or that western governments don’t stoke unfair narratives as well. That is also not to say Russia doesn’t deserve to offer its perspective and media services like other external actors, but it should do so legitimately.

Russia and its news agencies should be more transparent about the purposes of their media operations in Africa. The Kremlin should have greater respect for an independent and free Russian press to operate in Africa on its terms. They should simply stop trying to distort a narrative that serves their interests. But this describes an ideal world view, which we probably shouldn’t expect to happen anytime soon. My underlying point is that It’s one thing to provide a perspective, it’s another to instil disinformation and destabilise African countries’ political systems.

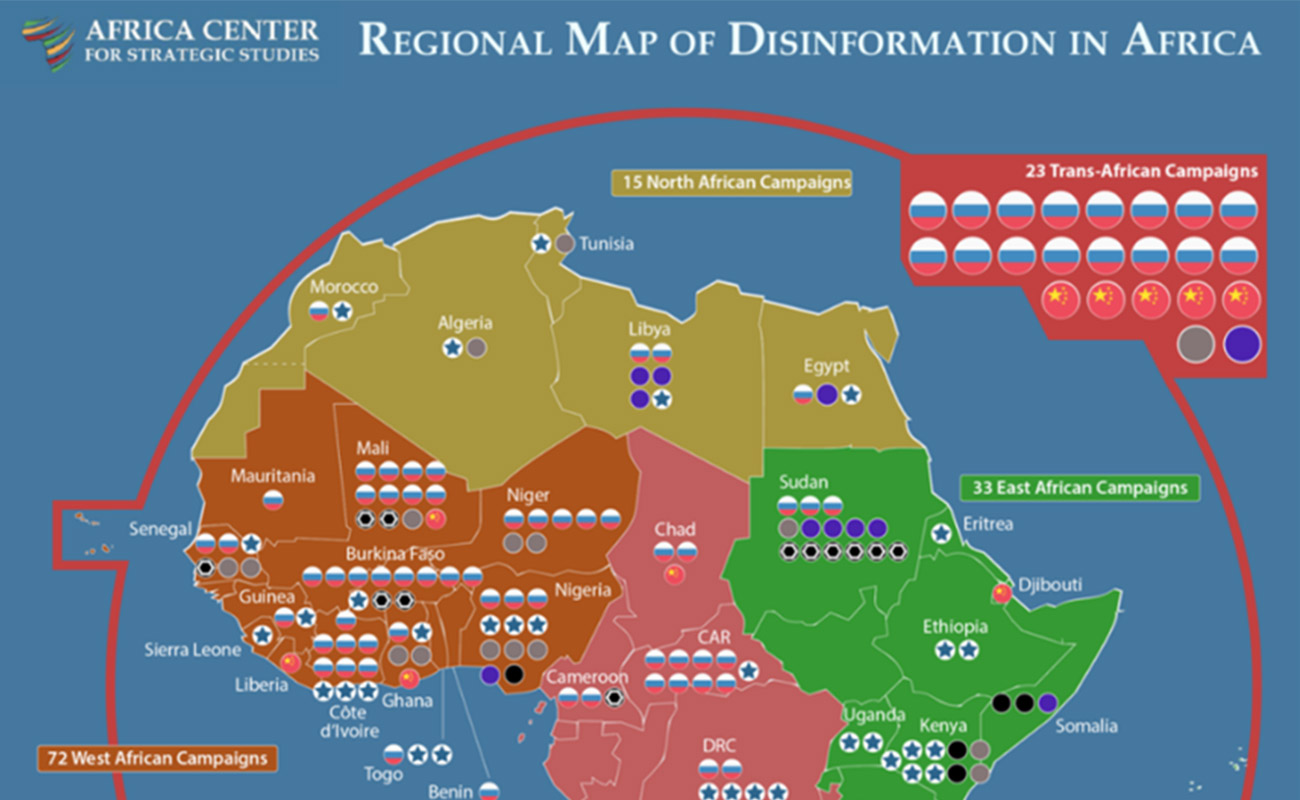

The diagram below produced by the African Centre for Strategic Studies illustrates the extensive scale of Russian misinformation.

African governments need to address this. However, to make such a statement might be unpopular since many African countries have either historically maintained harmonious ties with Russia since the cold war (e.g. South Africa) or are further aligning themselves as close partners of Russia (e.g. Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger).

In South Africa, we see at least six Kremlin linked actors, and Russian state-controlled news network RT has opened an office there, an agency that has already been banned in several western countries.

In Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, we’ve seen Russian flags repeatedly displayed in the streets during military coup takeovers in these countries. Sadly, matured democracies such as the U.S, particularly under Trump, are equally undermining freedom of the press in their countries.

Further, despite pro-Russian governments, there is still an interest in countering Russian misinformation in Africa. As U.S. Africa Command General Langley claimed, according to a National Security News article, ‘African leaders from every corner of the continent have voiced growing concern about the destabilising effects of Russian disinformation on their countries’.

How then should African governments challenge Russian misinformation?

The first way should be through education. As outlined in this LSE blog, ‘properly educated voters are essential to functioning democracies, but propaganda narratives conceal the truth, which results in disappointment, numbness or a poor choice of political strategy.’

Schools teach or should continue to teach more young people, who are arguably more receptive to misinformation, how to think critically and independently. That is not to say they should be taught to think negatively of Russia, but rather young people should be given the tools to develop independent opinions of Russia and other (geo)political issues.

The second way must be done via social media. A report by the African Centre for Strategic Studies notes that there are now more than 400 million active social media users and 600 million internet users on the continent. This is where a significant amount of Russian misinformation takes place, and it is particularly effective considering such campaigns focus on local communities’ issues and often speak in local languages or dialects.

To counter misinformation, governments should strengthen the powers and or capacity of national regulatory authorities. In addition, civil society groups should establish fact checking organisations. Ideally, platforms such as Meta (Instagram and Facebook) should cooperate with these groups. Other corporations should help fund these efforts. Promoting transparency and countering misinformation is not only a good corporate social responsibility effort, but it is also in their strategic interests, as often western corporations with operations in African countries are negatively affected by anti-western sentiments.

I may even go so far as to argue that Russian misinformation could pose a political risk to military juntas of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. While Russia may appear as an asset to the authoritarian and self-involved military leaders of these countries, Russian presence also poses a liability. While military juntas appear to be in control, they do not necessarily command the strategies and decisions of Russian media campaigns. This suggests that those in control of Russian misinformation could withdraw support or flip the narrative at any time, if these governments do not continue to offer concessions, such as votes at the UN General Assembly.

For the sake of not just democracy and stability as a whole, Russian misinformation needs to be addressed.