By Assam Francis

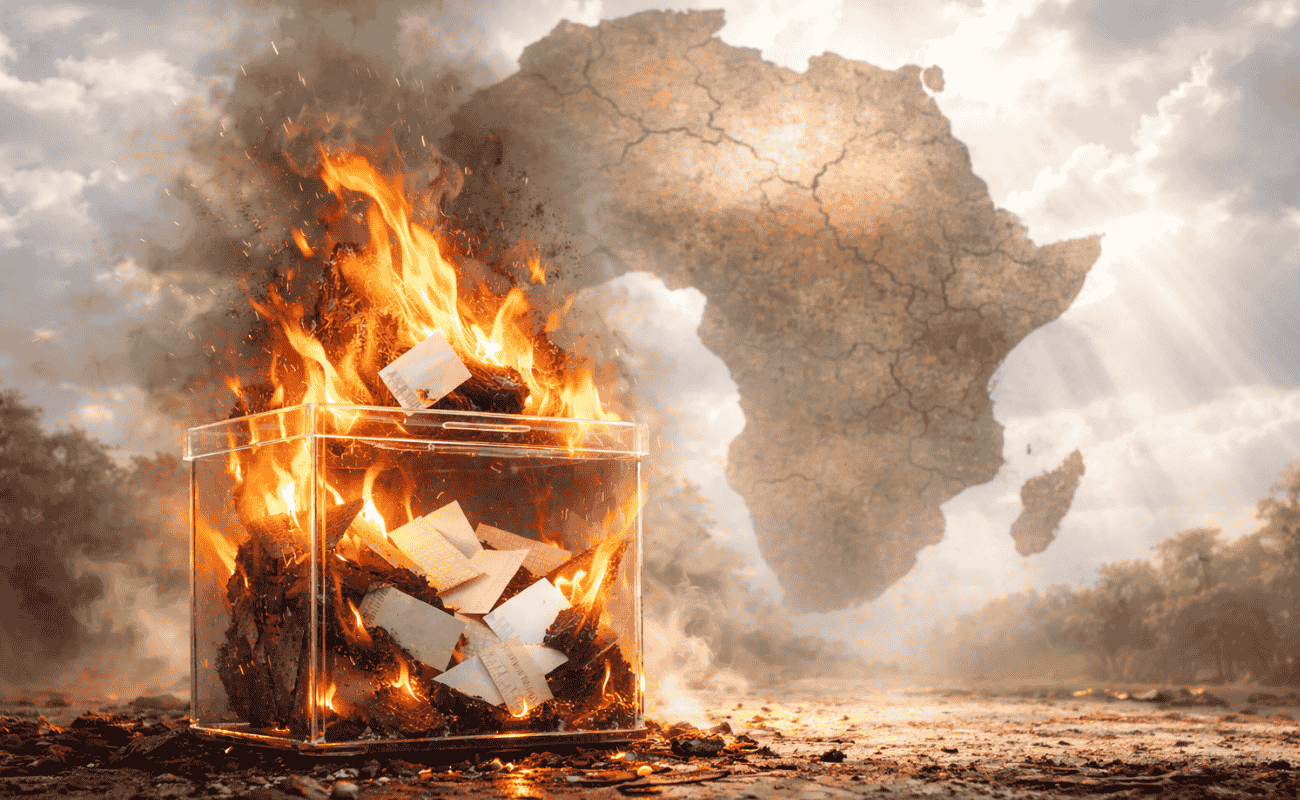

The recent attempted coup in the Benin Republic is more than just a headline; it is a warning sign that democracy is slowly losing its grip on the continent. A deep dive into this reveals that over the last decade, the relationship between African leaders and their citizens has fractured, revealing a dangerous shift toward authoritarianism masked as democracy.

The statistics are alarming. While 2024 saw over 20 elections across the continent, it also marked a rise in authoritarian tactics. This trend bled into 2025, where flawed elections in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Cameroon triggered massive protests. We are watching a pattern of constitutional coups, where leaders like Alassane Ouattara of Côte d’Ivoire and Faure Gnassingbe of Togo re-engineer state laws to extend their rule. The citizens bear the scars of this ambition, facing police crackdowns, injury, and death simply for demanding fair governance.

I always ask myself, where did Africa get it all wrong with democracy? It is a system meant to reflect the mandate and the voice of the people, yet in many states, the mandate is stolen. The frustration is so deep that citizens now take to the streets to celebrate military takeovers. The military is no savior. History has taught us that, but they are increasingly called upon to rescue failing democracies. A recent Afrobarometer survey confirms this: 53% of citizens believe it is legitimate for the armed forces to take control when elected leaders abuse power. Many African countries witnessed an appalling retrogression during past military regimes, so why call on them again?

Another aspect that has baffled me the most is how Electoral Management Bodies and the courts, institutions designed to be referees, have been used as conduits to manipulate electoral processes. Many African citizens no longer believe in the power of elections or the judiciary. The events of 2025 in Mozambique, Cameroon and Tanzania proved that the people have lost faith in the ballot box and the gavel. Incumbent governments are fond of using the courts to rule in their favor, leading me to ask: does power truly belong to the people?

Overall, the institutions I fault the most are the African Union and regional bodies. These organizations suffer from a hypocrisy crisis. With obvious electoral irregularities and rising human rights violations, these bodies seldom act fast to condemn the leaders involved. Their silence makes it seem as if they only care about who retains power, not the well-being of African citizens. It is interesting to see how quick they are to condemn military coups, as seen with Nigeria and ECOWAS’s swift reaction to Benin, but remain silent when civilian coups occur through constitutional tampering. By failing to call out leaders who abuse their office, they signal that they are too quick to support and praise underperforming leaders.

Way Forward

Identifying the problem is only half the battle. If we want to salvage democracy in Africa, we must move beyond complaints and demand actionable solutions. I believe the path to restoration lies in three critical areas.

First, we must aggressively depoliticize our judicial and electoral systems. The independence of the Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs) cannot just be on paper. Appointments to these bodies must be removed from the sole discretion of the presidency and subjected to rigorous, transparent public vetting. Similarly, the judiciary must stop being plan B for unpopular candidates to secure power. We need legal reforms that make it harder for courts to overturn the clear will of the voters based on technicalities. If the referee is biased, the game will never be fair.

Secondly, the African Union and regional blocs like ECOWAS must evolve. They need to stop acting like an Incumbent’s Club. The current definition of a coup is too narrow. We need a new protocol that classifies constitutional coups, such as manipulating term limits or rigging elections, with the same severity as military takeovers. If a leader changes the constitution to stay in power, they should face the same sanctions and isolation as a general who seizes power with a gun. We cannot condemn the symptoms (military coups) while ignoring the disease (political exclusion).

Finally, we need to bridge the gap between democracy and development. I strongly believe that the clamor for military rule is borne out of economic desperation. Democracy must put food on the table. It must deliver jobs for the youth and security for the community. When elected officials focus on service delivery rather than self-enrichment, the citizens will defend democracy themselves. The youth, who are currently leading protests, must also be given a seat at the table, moving from street agitation to policy formulation.

Conclusion

Despite this dark trajectory, hope is not lost. Nations like Botswana, Ghana, and Mauritius continue to demonstrate that stable democracy and peaceful transitions are possible in Africa. They are proof that if we rebuild our institutions and respect the will of the people, the rest of the continent can get it right, too.